A newly designed vaccine may help stamp out remaining polio cases worldwide

The oral polio vaccine is most commonly used in the developing world, despite one big problem.

CDC/Alan Janssen, MSPH, CC BY

Public health organizations around the world have been fighting for global eradication of polio since 1988. Through massive vaccination efforts, the incidence of polio has gone down 99% since then, with the virus eradicated from most of the countries on Earth.

But there have been many setbacks.

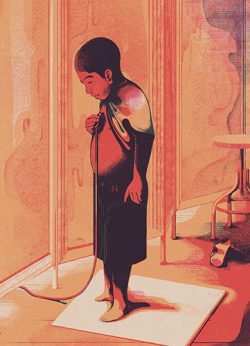

One particularly serious threat has surfaced over the last 15 years. Among poorly vaccinated populations, an increasing number of polio cases are due to strains of the virus that originate from one version of the vaccine itself. The Sabin vaccine, which is taken orally, is composed of live but weakened viruses that won’t sicken recipients but will still create lasting immunity against polio.

However, through genetic changes, the weakened vaccine virus can reacquire the ability to cause paralytic polio. How this happens and how to prevent it are under active research. A new vaccine deliberately constructed to prevent the poliovirus from regaining virulence may be the answer.

Virus in vaccines, attenuated or killed

The virus that causes polio infects the cells of the throat and intestine. People usually catch it by ingesting food or water contaminated with fecal matter from an infected person.

Most people infected with the polio virus have no symptoms at all; about a quarter of infections result in flu-like symptoms. However, in about 1 out of every 200 cases, the virus invades the cells of the central nervous system, causing paralysis.